ALEX COLLIS - NARRATOLOGY FOR GAMES COURSE – YEAR 1 - SEMESTER 1 - ESSAY SUBMITTED

NARRATOLOGY ESSAY _ ANALYSE A MODERN COMPUTER GAME

GAME CHOOSEN: FIREWATCH

The game chosen for this essay is Firewatch, which is a first-person action-adventure narrative lead, linear, open-world role play game (RPG; Campo Santo, 2016). The introduction for Firewatch mimics the non-linearity of films; for example, “Pulp Fiction”. Firewatch does this to keep the player’s engagement while it does a “Star Wars” like scrolling text at the beginning. This is split up with the beginning tutorials, such as interacting with objects and moving around the environment.

The two narrative structure theories being compared to Firewatch are Hero’s journey (Campbell, 1968) and Freytag’s pyramid (Freytag, 1911). Hero’s journey is made up of 17 stages: Call to Adventure; Refusal of the Call; Supernatural Aid; The Crossing of the First Threshold; The Belly of the Whale; The Road of Trials; The Meeting with the Goddess; Woman as Temptress; Atonement with the Parent; Apotheosis; The Ultimate Boon; Refusal of the Return; The Magic Flight; Rescue from Without; The Crossing of the Return Threshold, Master of Two Worlds, and Freedom to Live (Campbell, 1968). Campbell based his theory on mythological stories by analyzing them and creating the 17 stages that happen in most, if not all, the stories he researched to make this theory. Freytag’s Pyramid is made up of 6 stages: Exposition; Inciting Incident; Rising Action; Climax, Falling Action, and Resolution (Freytag, 1911). Freytag’s Pyramid theory was made by deconstructing dramatic structures of the time and basing it around the conflict of the hero and the adversary.

The two character structure theories being compared to Firewatch are Jungian and Propp character structure theories. Propp’s character structure theory is made up of 8-character archetypes: The villain; The Dispatcher; The Helper; The Doner; The Princess; The Oracle, The Hero, and The False Hero (Propp, 1928). To make this theory, Propp used 100 Russian folk tales and realised that every key character fits into one of these character archetypes. Using this theory in 2021 is quite problematic as the evolution of narratology means that characters do not always fall into the character archetypes. Carl Jung’s character structure theory called Jungian (Jung, 1919) is made up of four-character motivations: Ego, Order, Social and Freedom. Each motivator has three archetypes below them: Ego, Soul, and Self. Carl Jung believed in the theory of “collective consciousness” where the collective beliefs, ideas and emotions are driven by the collective whole of society. This influenced Jungian theory as it categorises people and characters into their core motivators.

This section will be about exploring the relation of the Hero’s Journey to the narrative structure of Firewatch, to determine the comparability of the theory to the game.

Campo Santo's decision to abruptly end the game at the 13th stage (The Magic Flight) is both a narrative decision and a technical one as well. Throughout the course of Firewatch, the player is presented with simplistic A or B decisions that give the illusion of player choice. However, the player is always pushed subconsciously or otherwise to do what the game wants the player to do. Firewatch's themes of isolation and disrupted relationships work well with the videogame medium as it compliments both the narrative contract(narrative of the game) and the ludic contract (gameplay of the game) of Firewatch as explained by Davidson (2018). Davidson (2018) explores the significance of the two contracts compared to BioShock and how if the contracts do not align in ideology it will result in ludo narrative dissonance(conflict between the narrative and gameplay). Firewatch’s ludo narrative synchronicity is supported by the dialogue, which would usually contribute to ludo narrative dissonance in other games. However, because of the themes of the game, it allows for the narrative’s trajectory to be unaffected by the player and therefore be able to go through 12 of the 17 stages unhindered . Every action a player has to the dialogue is accounted for with a reaction even if the player ignores the dialogue; it would still be in line with what Henry the character might do in that situation. This allows for a linear experience that follows the most cited version of the hero's journey up to the 13th stage.

Comparing the hero's journey to Firewatch shows that only 13 of the 17 stages work as the last 4 stages are not applicable because the game ends at the stage “the magic flight”. An adaptation of the hero’s journey by Vogler (2017) shows the flexibility and mailability to form differing perspectives of the format. Campbell’s clearest outline for the structure consisted of 31 stages, close to double that of the most cited version, which has 17 stages; both these versions are from Campbell (1968). If all 31 stages were used in a story or myth, it would be redundant as the 31 stages consist of every narrative element that Campbell thought was relevant in a story. Campbell did not think that every story would house every stage; rather, every story would consist of a handpicked few. The comparability of the hero's journey narrative structure to Firewatch’s narrative shows how even though it does not use all the stages they are still applicable.

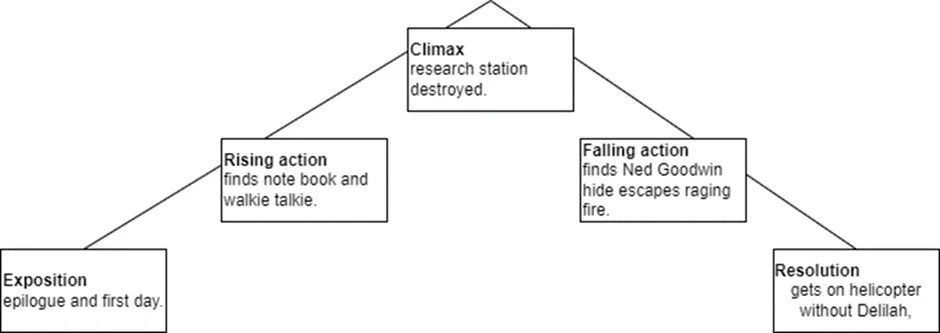

This section will be about exploring the comparability of Freytag’s pyramid narrative structure (Freytag, 1911) in relation to Firewatch’s narrative. Freytag’s pyramid, on the surface, is a simplistic narrative structure guide for linear narratives. However, it is like a skeleton holding up the structure of the story whether it be an epic space opera like “Star Wars” or just a simplistic adventure story like “The Peanut Butter Falcon”. The structure does not dictate what must be in the narrative like Cambell’s theory, it merely makes sure that the story stays on track and does not lose the interest of the audience. Comparing Freytag’s narrative structure to Firewatch’s narrative is an easy task, as Firewatch is a linear narrative whose lucid contract does not interfere with the game's narrative, allowing for a concise experience that follows Freytag's Pyramid quite well.

The only flaw in the comparison of the two is that Firewatch’s ending is ambiguous and can blur the line of the “Falling action” and the “Resolution”. This results in a divisive ending to a quite formulaic narrative that has led to some reviewers calling it a copout and cheating the player out of a fulfilling concise experience (Andrews, 2016; Kelly, 2016).

This section will be about exploring the comparability of Firewatch’s characters to Jungian character theory. Firewatch is a character-driven experience; however, the only physical character seen in the game is a firefighter on the rescue helicopter at the very end who does not even say anything. The main characters in the game that drive the story forward are the player character (Henry), Delilah and only minimally Brian’s father. Carl Jung’s character structure theory called Jungian (Jung, 1919) was created when narrative had not yet crossed over to interactive medium so it was not equipped to be flexible and react to the player’s interactions. It was made for a more linear medium of narrative. Brian’s father works well with Jungian character theory, as the player does not interact with the father who the player only hears as a voice message and receives letters from him. This allows the character to be more stable in their portrayal, compared to Delilah or Henry, who can change based on the player's interactions.

Jungian character theory states that every experience, action and emotion is dictated in a sense from a “collective consciousness”.Collective consciousness is a shared understanding of the social norms and practices of the culture that the person or character is from. The collective consciousness is broken down into character motivators and then in turn are broken down into three archetypes (as seen in the diagram).

The more concise decisions the player is presented with in a game, the more their collective consciousness is going to seep into a game and affect its outcome. However, a game can feed the player false choices (the distinction of two or more things when they are in fact the same), which can satisfy the player's need to interact with the narrative or characters while preserving the character's collective consciousness and in turn preserving the linearity of the narrative. Firewatch pushes the player through dialogue and other psychological tactics to give them false choices. An example of this would be in the beginning section of Firewatch when the player chooses a dog. The dog is brought up later in the game. However, the product of that interaction is identical and only there to give the illusion of the player's collective consciousness affecting the game. A physical false choice in Firewatch is when the player can burn down the research station. If the player chooses not to do so, it is burnt down anyway by Brian’s father and the blame is pushed on Henry (the player). Either way, the outcome is the same but it allows the illusion of the player's collective consciousness affecting the game. The Jungian theory works well with Firewatch, which is a deceptively linear game whose characters' collective consciousness is not altered by that of the players. This allows for the characters of Firewatch to fit into the archetypes and motivators of Jungian theory.

This section will be about exploring the comparability of Firewatch’s characters to Propp character theory (Propp, 1984). Propp’s character theory was created by condensing 100 Russian folk tales which found that every key character fell into one of eight character archetypes. These character archetypes are dated and lack the depth and complexity of the character archetypes of Jungian theory. However, a character can house multiples of these archetypes which allows the theory to account for more modern, complex characters but this can only go so far as it still is a dated character theory. Firewatch’s characters are much like real people as they are not inherently evil or good, they are just people trying to find some sort of happiness in a harsh, unforgiving world. Brian’s father kills Brian, not on purpose, but by an easily avoidable rock climbing accident. The distraught Brian’s father isolates himself from society, slowly going mad and hiding himself away. When he is discovered, he lashes out and tries to scare Henry (the player) away. Brian’s father is not a two dimensional character. He has his own twisted wants and regrets but he cannot be classed into a simple role as villain, as he is not evil; just misguided. Each character has their own wants, moulded into imperfect people - more real that what was designed for Propp’s theory. This is why Firewatch’s characters are not compatible with Propp’s character theory.

In conclusion, out of the four theories Campbell, Freytag, Jung and Propp only Propp does not work with Firewatch as it is too simplistic in its approach of character archetypes. Campbell’s character theory works to an extent as not every stage needs to be in a narrative for it to work. Freytag’s pyramid theory synchronises well with the narrative of Firewatch, with only the last two stages merging together towards the end of Firewatch. However, it still has more synergy with the narrative of Firewatch than that of Campbell’s Hero’s journey narrative theory. Finally, there is Jungian character theory, which works the best with the complex characters and linear narrative of Firewatch. Overall Firewatch’s narrative and characters present a complex and modern feat of design that may account for its commercial success and fan following.

References

Andrews, S. (2016) Firewatch Review. Available at: https://www.trustedreviews.com/reviews/firewatch (Accessed: 7 January 2022).

Ang, C.S. (2006) 'Rules, gameplay, and narratives in video games', Simulation & gaming, 37(3), pp. 306-325. doi: 10.1177/1046878105285604.

Campbell, J. (1968) The hero with a thousand faces. 2. ed. edn. Princeton, NJ: Univ. Press.

Campo Santo. (2016) Firewatch [0]. Available at: http://www.firewatchgame.com/ (Downloaded: .

Davidson, D. (2018) Well Played 1.0: Video Games, Value and Meaning Figshare.

Freytag, G. (1911) Die Technik des Dramas. Leipzig: Hirzel.

Kelly, A. (2016) Firewatch Review. Available at: https://www.pcgamer.com/firewatch-review/ (Accessed: 7 January 2022).

Propp, V. (1984) Theory and History of Folklore. U of Minnesota P.

Vogler, C. (2017) 'Joseph Campbell Goes to the Movies: The Influence of the Hero’s Journey in Film Narrative', Journal of genius and eminence, 2(Volume 2, Issue 2: Winter 2017), pp. 9-22. doi: 10.18536/jge.2017.02.2.2.02.